As told through the career journey of US Navy Nurse Corps Captain Pamela Kilmartin, CRNA, MSNA, APRN

A Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA) serving with the US Navy Nurse Corp and US Naval Reserve, Captain Pamela Kilmartin is a clinical consultant to Thornhill Medical, contributing valuable experience and insight to the company’s training and field operations.

Capt. Kilmartin recently revealed some of her incredible experiences from a 25+ year career providing life support and anesthesia in highly challenging environments.

In describing six compelling scenarios in which she and her critical care peers faced formidable hazards – from white-knuckle flights with oxygen tanks running low to ICU power outages during a hurricane to the COVID-19 pandemic and more – Capt. Kilmartin shares valuable ‘real-life’ perspectives on the role that compact, portable technology can play in en-route and prolonged casualty care in extreme environments.

Don’t miss Capt. Kilmartin’s perspectives on Anesthesia in Austere Conditions.

Cleared for take-off ― and rough landings

Transporting gravely ill or injured patients often means flying with vital-but-dangerous oxygen tanks – a serious hazard, especially during bumpy landings.

The pressure of “oxygen math”: lengthy flights and unplanned fuel stops

En-route care demands precise calculations of O2 consumption and supply. What happens when midflight delays put the patient’s oxygen supply at risk?

Drama in the ICU: power outages and flooding amid a hurricane

A hurricane triggers cascading crises in an off-shore ICU. It’s an all-hands-on-deck scenario for Capt Kilmartin and her peers when the power and O2 runs out.

Shipping out: en-route patient care on and off US Navy hospital ships

A humanitarian mission tests the limits of critical patient transport and mobile surgical care aboard the USNS Comfort.

Operation Enduring Freedom and the challenge of equipment load

Burdening the sickest and most critically injured patients with a cumbersome array of medical equipment complicates the care role during transport.

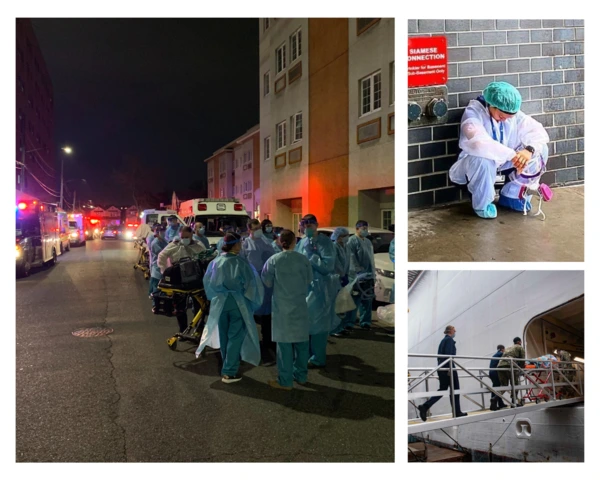

Pandemic response: O2 in buildings of opportunity and transport

As the COVID 19 crisis threatens to overwhelm global health systems, emergency and enroute oxygen supplies are in high demand.

Cleared for take-off ― and rough landings

“As a Board-Certified Emergency Room Nurse, I was eager for more adventure and excitement, so I ventured into Critical Care Fixed Wing Flight Nursing. The start of my career had me flying around the world to bring home patients from traumatic events or medical mishaps.

There was no shortage of challenges in transporting critical equipment to care for the ill and injured in remote and often underdeveloped locations. These included cumbersome and heavy equipment comprising transport ventilators, monitoring equipment, medications, and the always-needed oxygen (O2).

Whether we were in a small, fast Lear Jet or the slower Cessna, landing on a remote, bumpy airport runway would have me closing my eyes and gritting my teeth, knowing the huge H-cylinder of precious-but-dangerous oxygen was right next to me. This large O2 tank was necessary for the long transportation of ventilated patients, but it represented a serious flying hazard, especially during those bumpy landings.

Having access to the MOVES® SLC™ – which has an O2 concentrator and O2-conserving ventilator that together eliminate the need for heavy, dangerous oxygen tanks – would have made critical care transport, monitoring, and ventilating of my patients much easier and safer.”

The pressure of “oxygen math”: lengthy flights and unplanned fuel stops

“The time constraint associated with oxygen supply is always a challenge. Some flights were 12 or even 16 hours long, either in a Cessna, which is an unpressurized aircraft, or in a pressurized Lear Jet. O2 consumption during flight is a persistent challenge, affected by flight duration, altitude and unique needs of the patient.

On a long flight from South America to Maine, we had to make an unplanned fuel stop. I had calculated the hours of flight time and consumption required by the patient to maintain his O2 saturation, but it was clear that with the extra stop, we would run out of O2 by the time we landed in Maine thousands of miles away.

I messaged the pilot with a request for extra O2 to be delivered to the aircraft when we landed. This was before flight-to-ground communications were easily available, so we were relying on radio-to-air-traffic-control-tower comms to pass on the request quickly and accurately. An O2 concentrator integrated into the ventilator would have mitigated the risk of running out mid-flight and the safety issues of transporting O2 in the aircraft.”

Drama in the ICU: power outages and flooding amid a hurricane

“Fast forward a few years and I was working night shift as an ICU nurse in South Florida. We were in a small remote area off the coast in a brand-new facility that appeared to be well-equipped. One night, a tropical storm developed quickly into a CAT 2 hurricane. Without the instant information that we have today, there was no way for our team to know what was coming.

We were ―of course― short-staffed that night, with two nurses in the tiny ER, and five nurses caring for ten vented ICU patients. As the storm intensified, the hospital lost power, and the generator kicked in, setting off every alarm at the same time! With no way to transport patients to the mainland, we had to quickly prioritize what to put on the single red outlet in each room that was powered by the generator - something of a design oversight considering every piece of equipment in an ICU is important! The only item with battery power would be the IV pump, assuming it was already plugged in and fully charged.

Running around in the dimly lit ICU, we ensured everyone’s ventilator was in the red plug, and we chose to rotate the bedside monitors, plugging it in while we had the IV pumps on battery. When we were at the patient’s bedside, we would turn off the monitor and charge the IV pumps while we visually monitored the patient.

If that wasn’t enough of a challenge, soon we discovered that the hospital was on very low ground; in less than an hour, the generators and O2 supply for the entire facility began to flood. Using only our personal pin lights and the one flashlight in the ICU, we began hand-ventilating every patient on room air until we could get some portable O2 into the ICU. With only 5 nurses for 10 vented patients, this was no small task. Everyone pitched in; we employed the only respiratory therapist on duty that night, plus the house supervisor, one housekeeping personnel, and a security guard, all hand-ventilating patients who were becoming more aware as the IV pump batteries ran down and their sedation began to wear off.

Unplanned, cascading incidents such as power outages and generator and central O2 failure have serious implications, and are a prime use case for mobile, battery-powered, integrated technology like MOVES® SLC™.”

Shipping out: en-route patient care on and off US Navy hospital ships

“A few years later, I embarked on a new chapter of my career, becoming a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist and joining the United States Navy Reserves. I joined teams providing humanitarian care in remote locations, including almost 2,000 surgeries throughout ten South American countries over six months. Most surgeries were performed on the USNS Comfort TAH-20, one of two US Navy hospital ships to which patients were transported for care. Where a country’s ports could not accommodate such a large vessel, we would be located 30-50 miles off the coast in deeper water. This meant flight operations to get patients on and off the ship. Some patients required highly complex surgeries and further hospitalization after we departed, which meant critical care flight transportation to neighboring towns with larger hospitals – carrying multiple pieces of heavy equipment and oxygen tanks.”

Operation Enduring Freedom and the challenge of equipment load

“Ten years into my US Navy career as a CRNA, I was mobilized to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. It was there that I saw the Air Force Critical Care Air Transport Team (CCATT) in action. Daily we were either receiving critically injured patients from the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan or we were preparing critical care patients who had been stabilized just enough to fly to one of the large Military Treatment Facilities stateside, such as Brooke Army Medical Center or Walter Reed. The CCATT teams were fully equipped to take care of the sickest and most critically injured patients, but this nonetheless required multiple pieces of heavy, complex equipment, including ventilators, monitors, suction, and oxygen tanks. The patients would arrive with so much equipment mounted over them that you could barely see them! And with patients on flights of varying duration, there were many O2 tanks to transport as well. Again, this is an example of how integrated tech that eliminates multiple pieces of equipment and O2 tanks could benefit patients and care teams.”

Pandemic response: O2 in buildings of opportunity and transport

“In 2020, I relocated to New York City as part of the mobilization of the US Navy and US Army in support of the COVID-19 pandemic response. Local hospitals were overwhelmed with critical care patients requiring ventilator support, and the Javits Convention Center had been converted into a makeshift hospital during the crisis. Converting “buildings of opportunity” into temporary medical facilities is a common tactic used in humanitarian and/or combat scenarios but securing a safe and consistent supply of oxygen is not always easy.

Using portable O2 generators provided by the US Army, we were able to fill the many O2 tanks to care for COVID-19 patients. Soon it became clear that continued care would be required, so O2 was piped in for use in the makeshift ICU, bringing with it challenges and safety issues.”

“What’s more, many patients requiring ventilation had to be moved. I personally provided daily critical care transport throughout NYC from hospitals to other facilities with available ICU beds or even the USNS Comfort, which sat docked in NYC Harbor.

One night, one of the older hospitals lost its ability to generate oxygen. Within two hours, nearly 50 ventilated patients were transported to the USNS Comfort by US Army and US Navy CRNAs with Army Medics and Navy Corpsmen. But only a few high-tech ambulances were equipped to generate their own O2 and power; the rest relied on portable ventilators and O2 tanks. With the city’s hospitals and temporary facilities like Javits facing high demand for O2, there was only so much of it available for transport. It is another example of a scenario in which MOVES® SLC™ would have made a difference in the care of our patients.”

As evolving military and humanitarian scenarios bring new and complex demands in trauma care and patient transport, Thornhill Medical is proud that our life support technology MOVES® SLC™ and MADM™ can enable crtiical care providers to extend capabilities in a wide range of austere and far-forward scenarios. Learn more about MOVES® SLC™ here.

Capt. Pamela Kilmartin

A Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), Pamela Kilmartin serves as a Captain with the United States Navy’s Reserve Nurse Corps and is a member of the Navy Reserve Naval Medical Forces Development Command. Prior to becoming a CRNA, she was a Certified Emergency Room Nurse working in emergency trauma and civilian critical care fixed wing flight nursing. She teaches resuscitative medicine classes throughout Navy Medicine, including the Trauma Nurse Core Course and Tactical Combat Casualty Care.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest contributor and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of the US Navy, US Naval Reserve or other such organizations. The appearance of US Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.